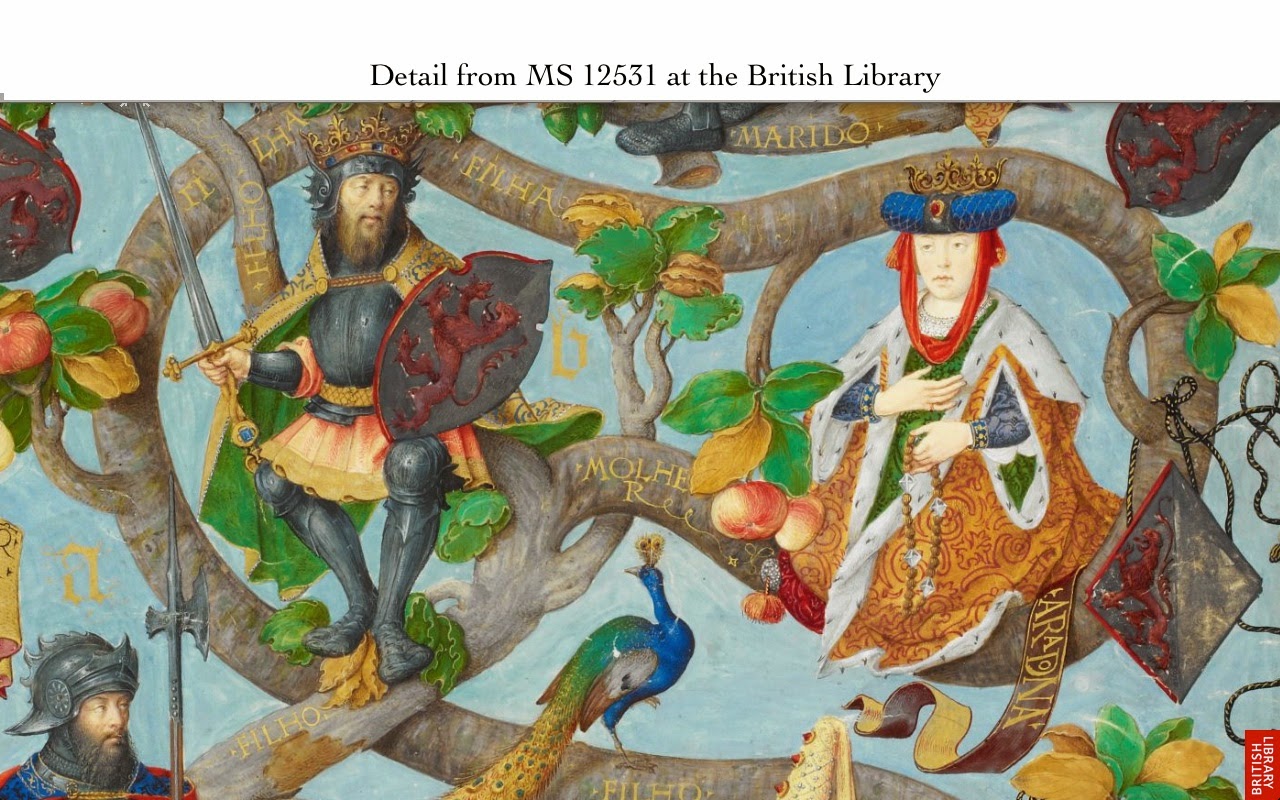

|

| Things, and the preservation of things, was as important in the Middle Ages as today. Image from a 15th-century edition of Boccaccio's Decameron. |

The conference opened with what was for me the highlight of the event: a plenary discussion by the esteemed professor, Caroline Walker Bynum. I had just begun reading what is considered one of Bynum's most important books, Holy Feast and Holy Fast (1987), a book that recounts the fascinating role of food in medieval religious practice, particularly among women. After reading only the first chapter of this text, I knew I wanted to hear her speak in person, and am so glad I had the opportunity - Professor Bynum delivered a dynamite presentation.

Her talk began with a paradox: the world's best preserved Catholic reliquaries and altars are to be found today, not in Rome or Castile, but in Protestant Saxony. While it is true that Rome's and other historically Catholic countries' museums are bursting with medieval objects of devotion, they are no longer in situ, a fact which changes their context and thus our ability to observe how medieval communities interacted with these objects. To illustrate this point, Bynum traced the histories of three particular objects of devotion that reside today in their original medieval location, Saxony, beautifully preserved.

|

| "Holy Blood Altar" in Rothenburg. The center cross contains the relic. Image source. |

She began in Rothenburg ob der Tauber, the location of the "Holy Blood Altar." This magnificent altarpiece was hand carved in the 15th-century by Tilman Riemenschneider, and features Judas as the central figure. The monstrance of this altarpiece was at some point replaced with a cross, delicately constructed to hold a crystal receptacle containing a small amount of Christ's blood. The continued and undisturbed presence of this relic as part of a main altarpiece complicated previous periodization theories of Protestantism's entrance into Saxony.

Bynum explained that some scholars have ventured explanations for this curious persistence of Catholic practices in Protestant areas of Europe throughout early-modern history by studying Martin Luther's teachings. Luther believed that objects had no inherent sacrality and that likewise, images (art), were indifferent. This objection to the use of religious iconography as an integral part of worship accompanied by a staunch opposition to any form of iconoclasm. This has lead several researchers to posit what they consider a particularly Protestant method of "accidental" preservation: as the image is neither sacred nor a source of conflict, they must simply be left where they were found.

Bynum's talk put forth a more nuanced theory by demonstrating that while the "let it be" theory seems satisfactory on the surface, it begins to lose ground when applied to Catholic objects that were preserved, not by Protestant indifference, but by continued and intense interaction with these objects through worship.

|

| The Holy Sepulcher in the Wienhausen cloister church. Ignore the little red circle on the tomb - this was the only image online I could find! Image source. |

In the Wienhausen cloister in lower Saxony, a figure of the dead Christ with exposed wounds rests in a decorated tomb. The Christ figure was made around 1290, when it came into the possession of the nuns of the Wienhausen cloister, and remains there today. Several marks and even medieval graffiti on the figure indicate to art historians that this Christ was approached from the right-hand side by the congregation, on a very regular basis, for devotional practices including the anointing of his forehead. Though nailed down now, the figure is hollow and believed to have been processed in performative styles of worship. Furthermore, there is evidence that a reliquary bundle had been inserted into his head.

|

| St. Barbara, painted in the 15th century by the Master of Frankfurt |

Bynum had examined multiple historical documents from the cloister which revealed the intensity with which the nuns protected this figure and fought to keep it in their church. Several abbesses outright defied the direct orders of Protestant bishops, who had told the sisters to send the statute to a museum. The abbesses cited the strong devotion of the community as their reason for noncompliance. The continued use and vehement defense of this statue problematizes not only the periodization of Protestantism's entrance into Saxony, but also the reasons for the preservation of certain Catholic devotional objects and practices.

Towards the end of her talk, Bynum highlighted the practice of sewing and embroidering clothes for statues of saints and angels, a devotional practice surviving in parts of Saxony long past Protestantism's supposed entrance into the region. She displayed images of the beautiful garments, full of ornamental embroidery, created by the nuns of the cloister for their church's statuary. Each saint and angel had several different outfits, reserved for different feast days and special moments in the liturgical calendar. Tags were sewn into the garments with the saint or angel's name and the day on which they were to dress the statues with these particular articles of clothing. (Unfortunately, for all the wonders of the Internet, I was unable to find images of the beautifully detailed garments professor Bynum showed. She did, however, mention the Madonna of 115th Street as a modern example of a similar practice.)

In the end, Bynum pointed to a fundamental disagreement people had then and continue to have today over the meaning of objects and our interactions with them. While one school of thought proposes that, in dressing and manipulating objects in the ways described above, we subject them to our authority and demonstrate their lifelessness by exerting our power over them. On the other hand, the contrasting school of thought believes that these practices enhance the mystery and aura of an object, giving it more life than they would've had without our interaction and, in some cases, turn the objects into a material connection to the divine. This question, Bynum indicated, is at the heart of the debate over medieval devotional objects and that our ability to reconcile the two polar opposite schools of thought is likely related to our understanding of performance.

The remainder of the conference exposed the vast array of intellectual interpretations of medieval materialities, some related to devotion and others related to daily life: literature, architecture, gifts, birthmarks (!), pastimes. I believe, though, that each panel related back to professor Bynum's initial plenary session, by asking the question which ultimately needed to lay at the heart of a conference on Medieval Materiality: "What does the object do and, more importantly, what does it make me do?"

The conference was full of so many engaging discussions - hopefully a few more of them will make it onto the blog!

Until next time - keep rustling!

.png)

.jpg)